It is the year 2040, and the Crown has remembered its own handwriting.

After two and a half centuries of delay, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784 remains a constitutional dedication, not a treaty of convenience — binding the conscience of the Crown forever.

The judgment reads like prophecy fulfilled:

“The dedication endures. The heirs endure. The honour endures.”

But the story of how we reached this moment begins much earlier — in courts, classrooms, and institutions that spent generations erasing the very heirs they now recognize.

1. The Long Silence — Oak Park Road, 1990s

In the 1990s, a developer named Steve Charest bought a parcel near Oak Park Road in Brantford.

He didn’t know it was part of the Haldimand Tract — land promised to the Mohawk Loyalists for their “exclusive use and enjoyment forever.”

When land protectors occupied the site to protect it, Charest sued the city for failing to disclose those underlying rights.

Justice Lenz heard the case and ruled that once land had passed to “innocent third-party purchasers,” no right of dispossession could stand. Then he added, almost to himself:

“We haven’t seen those people in 150 years.”

It was a confession. The courts had forgotten the very people written into the law.

The City responded by rewriting its bylaws to disclaim all liability for “Indigenous or historical interests.”

The Crown’s handwriting faded further from its page.

2. The Institute of Substitution and the Scottish Talzié Principle

Before the law forgot, it had already been made to forget.

In the early 1800s, Six Nations Council, aligned with colonial administrators, granted land to the New England Company to build what became the Mohawk Institute Residential School.

On the surface it was a school. In reality it was a legal experiment in disinheritance — the first large-scale attempt to replace hereditary succession with administrative management.

In Scottish entail law, such hereditary succession is called a Talzié (or tailzie).

A Talzié is a deed of entail that locks property or rights within a specific bloodline, binding it forever to the heirs of entail.

The estate cannot be sold, traded, or converted. Each heir has a lifelong beneficial interest, but none can break the chain.

It was Scotland’s way of guaranteeing that a family’s inheritance could not be dissolved by politics, commerce, or government.

By granting land for the Mohawk Institute, Canada and its partners effectively broke a Crown Talzié.

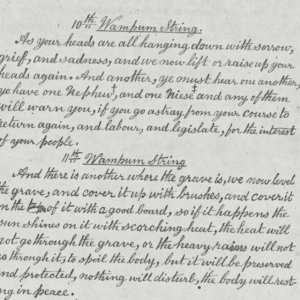

The Haldimand Proclamation functions as exactly that — a royal entail to Mohawk Loyalist posterity, a hereditary dedication binding as long as one descendant survives.

The Institute used the name “Mohawk,” but its purpose was to erase the record of the bloodline.

Children were trained to forget who they were descended from.

In trust law, this was intermeddling — taking control of an inheritance without lawful authority.

Those who ran it acted as trustees de son tort — trustees in wrongdoing — managing a hereditary estate they did not own.

The Talzié principle answers that wound.

It affirms that posterity cannot die while even one descendant breathes.

The bloodline continues whether the record shows it or not. And when heirs restore their line of proof — through the Dorchester Mark of Honour, Simcoe’s Heritage Registry, and Loyalist certification — they reactivate the Crown’s duty of observance.

The Mohawk Institute, in that light, becomes the monument of substitution — the moment a living entail was replaced by administration.

The Talzié restores it, proving that the line was never lost, only hidden.

3. 2024 — The Petition of Memory

In 2024, the question came back to life.

In a Brantford courtroom, I stood as Benjamin Doolittle v. The King. What began as a traffic matter became a constitutional challenge.

I asked for one thing: a declaration that the Mohawk Loyalist posterity — the true heirs of the Haldimand dedication — still hold exclusive use and enjoyment of the Grand River lands.

Justice of the Peace Richard Kwan refused to issue that declaration, explaining that Six Nations Band Council had filed for the same under their 1996 lawsuit.

He said their case would go forward first because, in his words, “they have more money and bigger lawyers.”

But the question was never about money — it was about standing.

Who has the right to speak before the law for the Haldimand Tract?

The administrative collective, or the hereditary heirs?

Days before, we had served the Band Council a cease-and-desist notice, stating that the heirs did not consent to having their hereditary rights turned into collective or Aboriginal claims. The Proclamation was not communal property — it was a hereditary dedication.

That moment drew the line in Canadian law between inheritance and administration.

4. Why Standing Matters

Standing is everything. Without it, the true inheritors of a promise have no voice in its defence.

When hereditary rights are mistaken for collective ones, sovereignty dissolves into administration.

That’s what happened in the 1970s, when Justice Osler ruled that the Grand River lands were sovereign — but his finding was overturned after Six Nations argued they held lands and funds “in trust” under the Indian Act.

That single appeal converted a living dedication into a managed estate.

For fifty years, the courts followed that path — until they rediscovered three ancient precedents.

5. The Three Cases That Resurrected Honour

(a) The Manitoba Language Reference (1985)

The Supreme Court ruled that laws made outside the Constitution were void from the start, though allowed to stand temporarily out of necessity.

In 2033, the same reasoning was applied to Ontario and Canada: any legislation that contradicted the Haldimand Proclamation was constitutionally invalid, but would stand until replaced by acts of restoration.

(b) McAteer v. Canada (2014)

This case confirmed that swearing allegiance to the Crown is swearing to the constitutional order itself.

In the 2030s, that principle was reversed back on the state: If citizens are bound to honour the Crown, then the Crown’s officers are bound to honour her dedications.

Thus, failure to observe the Haldimand Proclamation became criminal negligence in public office.

(c) Trustee de son tort

This old doctrine states that anyone who interferes with a trust without lawful authority becomes a trustee in wrongdoing.

In 2036, the courts found that Canada, Ontario, and the Band Council had all acted as trustees de son tort, managing a hereditary trust they did not own.

That finding tore open the door that had been closed for generations.

6. The Chapel and the Rosetta Stone

On a hill overlooking Brantford stands Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks — and within it, the bronze plaque unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II in 1982.

Its words appear in English, French, and Mohawk — three tongues, one covenant.

When the Queen unveiled it, she bypassed the Canadian government entirely.

It was a direct act of prerogative — a message from the Crown to her Mohawk allies.

That plaque became known as The Rosetta Stone of Honour, the key that reconnected the Crown and the Mohawk posterity.

7. The Doctrine of Dedication — 2038

When the Supreme Court finally heard Doolittle v. Canada in 2038, they issued the judgment that changed everything.

The Court declared that the Haldimand Proclamation was a dedication, not a treaty — an act of faith binding the Crown forever.

Citing McAteer, Manitoba Language, and trustee de son tort, they ruled that no statute or agency could override a constitutional dedication, and that any official acting against it became personally liable.

The Crown, for the first time in centuries, stood again on its word.

8. The Restoration of Honour

By 2039, Parliament enacted the Restoration of Honour Act, formally restoring the Grand River as a perpetual hereditary trust for the Mohawk Loyalist descendants.

A new office — Custodian of Honour — was created to ensure the dedication could never again be forgotten or misused.

9. Epilogue — The Heirs Remember

The judgment did not grant new rights.

It restored memory.

It confirmed that posterity cannot be substituted, that the Mohawk Institute’s shadow could not erase inheritance, and that the honour of the Crown cannot be delegated or sold.

Standing — the right to be seen, to be heard, to be recognized — was returned to those who never surrendered it.

And so, as the final line of the judgment reads:

The dedication endures.

The heirs endure.

The honour endures.

Benjamin Doolittle UE