Rights assertions, keeping chiefs in check and working to uphold consensus decisions are a part of the documented history of Six Nations

SIX NATIONS — The 1990s was a big time for activism among the Six Nations people.

This was the era where Canada, the US — and the entire world really — witnessed the resurgence of Mohawk sovereignty coming from the Women and the Warriors of the Kentyohkwahnhákstha families who were finding their voices again.

There was a divide among the Haudenosaunee people in the late 1980s, early 1990s that was playing out among the Mohawks. Those in pursuit of pushing the sovereignty envelope to secure economic growth were usually on side with the Warriors. Those in pursuit of morally maintaining the reserves and keeping reserves free of gambling and tobacco were usually on side with the conservative Gaiwiyo Handsome Lake followers.

This pro-/anti-Warriors vibe became evident during a dispute that was emerging in 1989 about gambling and governance at Akwesasne — a reserve community of Kanienkehaka that straddles Ontario, Quebec and New York State.

Through the late 80s, FBI conducted numerous raids on casinos run by Akwesasne people on the New York State side. The operations had become a big money-maker for the communities and the Mohawks were being accused of evading taxes.

RCMP raids were also coming down at that time at nearby Kahnawake over the Indigenous tobacco trade — which was another emerging economic rights assertion by the Mohawks.

Warriors were committed to resolving the economic strain of reserve life and saw hope in utilizing tobacco, casinos and bingo halls. At Akwesasne, six casinos ran under territorial sovereignty asserted by the Warriors to build an indigenous-governed economy, outside the restraints of foreign governments.

Warriors who were in support of using the casinos and bingo halls to build community wealth outside of federal rules were labelled by the press as a fanatical minority. A “pro-gambling, pro-sovereignty, heavily-armed Warriors” angle was levied by the media. The age-old scary Indian — the stuff of colonial nightmares.

In contrast the anti-gambling/anti-Warrior crowd emerged as opponents — making a moral objection to gambling. This faction was predominantly followers to the Gaiwiyo religion which counts gambling as one of the core major “sins” for lack of a better term. They blamed the Warriors for bringing social ills to the community. Those folks were framed by the press as the moral majority crowd who believed in the rule of law.

Anti-gambling/anti-Warrior folks were appalled that houses of ill repute were being established on the territory and took action to stop it, establishing barricades around the Akwesasne community and demanding the leadership find a resolution.

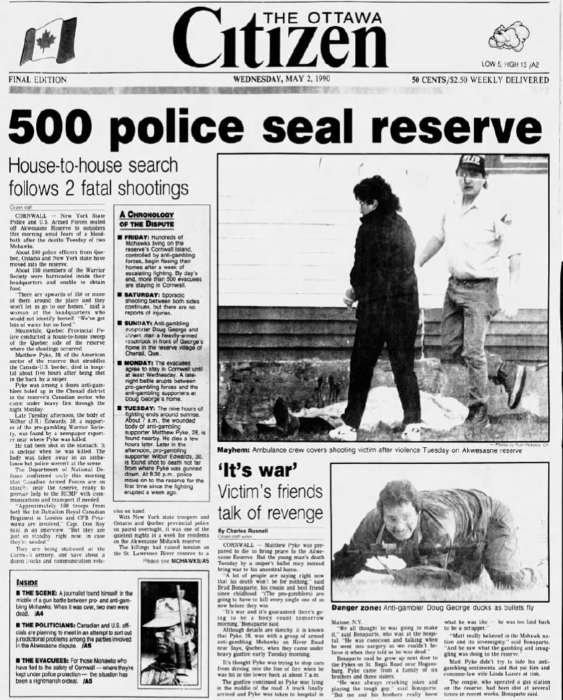

Eventually the pro-gamblers tore down the barricades and there was a series of violent outbreaks. Media reports slammed the Warriors, the Associated Press saying “pro-gamblers tore down the blockades in a hailstorm of gunfire”.

But in the great tradition of settler-meddling – there later emerged reports that anti-gambling, anti-Warrior folks were being supported by the Canadian and US governments and supplied with guns and ammunition that were paid for by the Surete du Quebec – the province’s police service.

This access to weapons and the existing tensions exacerbated a bad situation into a catastrophic explosion that led to a week-long violent confrontation and gun battle at the end of April 1990.

The old folks I’ve talked to called this Akwesasne’s Civil War. Two Mohawks were killed: 22 year old Matthew Pyke, who was described by the Associated Press as “anti-Warrior” and J.R. Edwards, who the AP reported as a “member of the Mohawk Warriors”.

By this time, approximately 2000 residents of Akwesasne fled their community and found shelter in a refugee centre on Cornwall Island. Because the community spans Ontario, Quebec, the US and Haudenosaunee territory there were jurisdictional complications to resolving the dispute and there was a multinational convention after the shootings. The military was called in from various sides to maintain the peace.

As a result of those meetings, the hereditary chiefs of Onondaga and Six Nations, who at that time were also predominantly Gaiwiyo religion supporters, issued a joint statement saying that anyone who takes up arms against each other is “outside the circle” and has no right to assert any treaty rights.

This was all taking place at the same time as the standoff at Oka was picking up. In March of 1990 the barricades went up at The Pines. The Mohawk people of Kahnesatake were taking a stand to protect burial sites that were at risk of being disturbed to make way for 60 luxury condos and an 18 hole golf course.

The morning of July 11, 1990, heavily armed police moved in to remove the people from protecting the Pines and the conflict began. A gun battle broke out between the people and the Surete du Quebec officer was shot and killed.

The response from Canada was to send in thousands of armed military. That only resulted in the calling in of Indigenous Warriors and supporters from across Canada and the US — and the eyes of every major media company with a camera from around the world.

Being a Warrior, or even Warrior-adjacent at this time, was not looked upon with pride but rather with a spirit of rejection and suspicion — especially on Six Nations.

The first Aboriginal Solidarity Day on June 21, 1989 was not a celebration, but rather a controversial event that had local schoolteachers afraid to participate for fear they would endure consequences from their employer if they took the day off work to participate.

I can remember a time when flying the Unity Flag, aka the Warriors Flag, was something that could get you socially punished on the rez. People were disowning family, cancelling jobs and refusing to work with anyone who flew that or any other type of flag associated with barricades, land rights assertions or otherwise.

Those beliefs even spilled over to native kids on the local elementary and high school busses who would either boo and hiss at houses that had Warrior flags flying in their front yards — or give the owners the thumbs up as they went passing by. Everybody and their kids was picking sides.

Those factional divides were present at Six Nations within the hereditary council. Take for example the reclamation of the Six Nations Old Council House in Ohsweken.

This was an initiative that was led by Six Nations men. Seven years had passed since the hereditary councils of Onondaga and Six Nations issued that 1990 joint statement condemning the Warriors — disinheriting them from any treaty rights. As a result, anyone who associated with or even empathized with “the Warriors” endured a lot of judgement and prejudice as they worked with the hereditary chiefs.

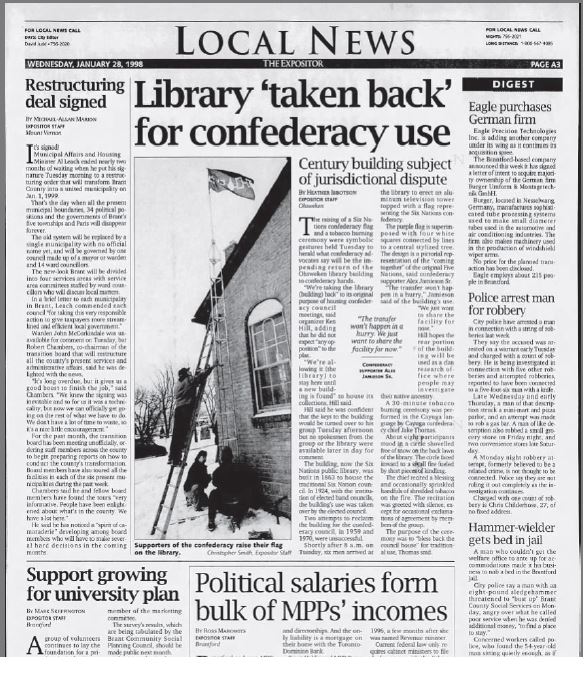

On January 27, 1998 — Onondaga Beaver Clan speaker Dehatgahtos, at that time a title held by Arnie General, went with Cayuga Chief Jake Thomas and 6 Six Nations men and women to reclaim the Ohsweken Council House. At that time, the council house was the home of the Ohsweken Public Library. General and Thomas were accompanied by a group of supporters including Gawitra Alex Jamieson, Sagoyesahta Ken Hill, Wendy Thomas and Lawrence Nanticoke.

The men delivered a letter to the Library staff giving them time to vacate the property, informing them the building was being reclaimed by the hereditary council, and raised a Hiawatha Belt flag above the building. Chief Jake Thomas did a tobacco burning outside the library, and called on the Peacemaker for help.

A few days later, the monthly meeting of the HCCC was scheduled and Dehatgahtos was publicly condemned for raising that flag. The Six Nations newspaper, the Tekawennake, reported the events of that meeting.

The criticism against General’s actions were spoken out by a Gaiwiyo faith keeper, Norman Jacobs. Jacobs is said to have started off the meeting by acknowledging that because there were no Seneca or Mohawk chiefs present that it was not an official Council — but held space for an unofficial conversation of what took place at the Old Council House.

The Teka writes that Jacobs scolded General, saying the Haudenosaunee did not have a consensus that the Hiawatha flag was a symbol of the Confederacy.

“A lot of people use the Hiawatha flag as a symbol — but it has never been accepted as the official, recognized symbol of the Confederacy,” said Jacobs.

The Teka wrote, “the majority of Confederacy members were against the gesture of the Beaver clan. Jacobs said that decisions need to be made by consensus, that the Peacemaker taught them to put away their weapons, and to use dialogue and communication to accomplish goals. He said that they must be of one heart, one body, and one mind, and when a clan goes off on their own, they are breaking the unity.”

Jacobs also condemned the actions of the Beaver clan — saying the Confederacy was owed back-rent for 63 years from the band council and that the actions of the Beaver clan was jeopardizing that money.

General was reportedly shocked and surprised at the reaction, but stood by his decision saying that the people were being criticized for doing nothing, and now they were being criticized for doing something.

General said, “It’s hard to judge peoples reactions, ‘cause the motivator is money. I know we need some, but do we need to sell our future for it?”

General was likely referring to a previous stand he took when the Onondaga Beaver Clan rejected to enter a treaty with the band council and the federal government a few years earlier.

In 1993, a proposal came to the hereditary chiefs to enter into a new treaty agreement with the federal government that would, in part, have given authority of education given to the HCCC.

That initiative was being led by an education committee who drafted an education law. The federal government was claiming they would not be paying for education for Six Nations after 1995 and that in order for any education funding deal to go through — the Six Nations hereditary chiefs council had to be party to the treaty.

The deadline came down to the wire in the summer of 1993. The clan families were given drafts of the law to review and a small group of dissenting clans — General’s Dehatgahtos Beaver Clan family— voted not to accept the education plan being offered by the federal government.

The Dehatgahtos’ clan family presented a brief, stating that the education plan being presented by the federal government was looking to the Six Nations land claim as justification for what it would use as collateral to fund education.

The Dehatgahtos people, and several other speakers for the Haudenosaunee clan families including Sam General from the Cayuga Wolf, Jake Thomas from the Cayuga Snipe and Richard Maracle from the Mohawk Bears — could not find consensus with the rest of the HCCC to agree to the terms being presented.

Their argument was that the federal government was already paying for education. Why does the hereditary council need to agree to settle the land claims for education funding — when the federal government was already paying for education?

Because of that position, and other items of disagreement by those clan families — consensus was not achieved and the matter ‘died’ on the council floor.

Arnie General was later quoted by the Brantford Expositor as saying that his family could not agree to the proposed agreement because working with the band council would undermine the Confederacy.

These are all acts of decolonization — carried out by the Women and Warriors of the Kentyohkwahnhákstha. These are the people who have pushed to build economic stability for our own people under the processes of the Great Law. Without the Women and the Warriors there would be no such thing as the Indigenous tobacco trade as we know it today.

The work they did to assert those economic rights was not led by the hereditary chiefs. In fact the hereditary leaders often condemned the use of tobacco to make money when the trade first began.

The efforts of the Women and the Warriors exercising their rights leads our traditional governance system and which way our communities will grow — on our own terms.

The families are not governed by a circle of chiefs. The families of the Kentyohkwahnhákstha are governed internally by virtue of a covenant promise to uphold the peace. The people exercise and hold our treaty rights including our sovereign right to build indigenous economies, education, health facilities and child welfare services to serve our own people.

No group, government, collective or foreign entity outside of the clan families of the Kentyohkwahnhákstha has any right to claim otherwise.