In 1784, the Crown granted the Grand River lands “for the use of the Mohawk Nation and their posterity forever.”

That covenant, confirmed by Canada in 1791, remains the constitutional foundation of this country.

The problem is—Canada forgot it.

When Governor Frederick Haldimand issued his Proclamation on October 25, 1784, he kept a wartime promise.

The Mohawk Nation, loyal allies of the Crown during the American Revolution, had lost their New York homelands.

To restore them “to the same state as before hostilities,” the Crown substituted lands along the Grand River “for the use of the Mohawk Nation and their posterity forever.”

When Canada confirmed that Proclamation on December 24, 1791, it accepted more than a gift of land—it accepted a constitutional obligation. In that moment, the Mohawk Nation and the Crown became the twin pillars of Canada’s legitimacy.

Remove either pillar, and the structure of the state loses its lawful footing.

A Misnamed Treaty

Modern institutions often describe the Haldimand Proclamation as a “treaty” with the Six Nations. It was not.

The Proclamation explicitly names the Mohawk Nation, inviting only that “such others of the Six Nations as may wish to settle among them” could join. In Wilkes v. Jackson—an 18th-century case involving the same instrument—the court confirmed that this phrase did not create a collective body politic. The rights were hereditary and individual, not collective. Hereditary Rights, Not a Band or a Clan The heirs named in the Haldimand covenant are not a political band, not even a single community. They are the posterity of the Mohawk Loyalists—families who stood with the Crown. Two and a half centuries later, those descendants are diverse and global. Some live on the Grand River; others might live unknowingly in London, Beijing, or Nairobi.

Their rights are hereditary, not ethnic. Because the covenant is a royal legal instrument, its beneficiaries are defined by lineal proof, not by clan systems or Indian Act registration. The Haldimand document was drafted under European legal logic—akin to a lettre patente—and created a distinct class of Loyalist Mohawk posterity

whose entitlement is juridical, not administrative.

That means the Six Nations Band Council, or any list created under the Indian Act, cannot lawfully claim “exclusive use and enjoyment” under the Proclamation. It lacks completeness; it cannot represent every heir. To treat it as the rights-holder is to disenfranchise the many descendants—wherever they now live—who carry that lawful inheritance.

Dorchester’s Correction

Recognizing the flaw in the Proclamation, Lord Dorchester in 1789 established a formal system to verify Loyalist descent: those who could prove lineage were entitled to append “U.E.” (Unity of Empire) to their names.

This was the Crown’s administrative solution to the “fatal flaw” of unnamed beneficiaries. The United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada (UELAC) continues that role today. It remains the Crown’s only lawful process for verifying hereditary descent and confirming who the “posterity” are. No band list, registry, or collective claim can override that original verification.

1924: The Year of Erasure

In 1924, Ottawa amended the Indian Act, abolished hereditary councils, and installed an Indian Act Band Council at Six Nations.

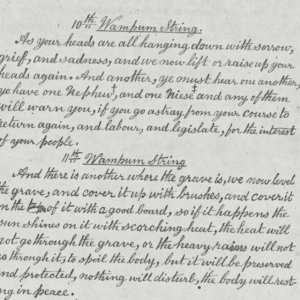

RCMP officers raided the council house, seized wampum belts, genealogical records, and meeting minutes—the physical proof of descent—and declared the traditional government “dissolved.” That act replaced lineage with registration, and heritage with administration. Roughly 300 Mohawk Loyalists petitioned the Governor General that same year, invoking their rights as Haldimand posterity. The Crown acknowledged their standing, but Ottawa buried the implications. Since then, the covenant has been treated as a relic rather than the constitutional cornerstone that it is.

The National Shadow

Canada’s political psyche carries a shadow: its denial of the covenant that made it legitimate. Every land acknowledgement, every reconciliation pledge, is haunted by the omission of the words “Mohawk Nation and their posterity.”

Universities repeat the misstatement that the Haldimand Proclamation was a treaty to “Six Nations,” perpetuating historical inaccuracy and legal confusion. Municipalities tax property that legally belongs to Mohawk posterity. Even Canadian citizens, by swearing allegiance to the Crown, are bound to uphold a constitutional order that includes this covenant—but most have never been told.

The Law Remembers

Under Section 52(1) of the Constitution Act (1982), any law inconsistent with the Constitution is void. The Manitoba Language Reference confirmed that unconstitutional frameworks may function only under temporary necessity, not legitimacy. By that logic, any title, permit, or public work on the Haldimand Tract issued without Mohawk consent is constitutionally defective.

Recent cases on fee-simple defects and unjust enrichment reaffirm this principle: no downstream purchaser can “cure” a defective root of title. When the defect is constitutional, the only cure is consent—or restitution.

Restoration, Not Rebellion

Restoration is not removal—it’s legality. It means reinstating Dorchester’s verification process, recognizing the exclusive use and enjoyment of verified Mohawk posterity, and converting occupation into leasehold, compensation, or consent-based tenure.

Universities, corporations, and municipalities can remain, but lawfully—under the covenant they stand upon.

To restore the Haldimand Covenant is not to undo Canada. It is to restore the balance that made Canada possible.

Closing Reflection

Inside the community, the word “Loyalist” still carries stigma. Outside it, the covenant is forgotten. Yet Queen Anne’s communion set, Queen Elizabeth II’s 2010 silver bells, and the enduring “U.E.” designation all testify to a 300-year alliance still in effect.

To deny that covenant is to deny the honour of the Crown itself. To restore it is to fulfill Canada’s first and most sacred constitutional duty.

Loyal then. Loyal now. Loyal forever. The honour of the Crown still rests on the river it promised to the Mohawk Nation and their posterity forever.