By Jim Windle with notes from Paul Williams

SIX NATIONS – Did the Haudenosaunee give away a huge chunk of land in 1701? There is much confusion and misunderstanding over what is known as the Nanfan Treaty, or more accurately, the Fort Albany Treaty of 1701. Some say it only covered hunting and fishing rights, but a deeper study shows that it was a lot more than that.

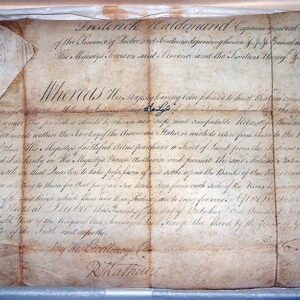

The wording of one section within the Treaty is especially troublesome for today’s Canadians and Haudenosaunee people alike. It reads (including old English spelling) as follows:

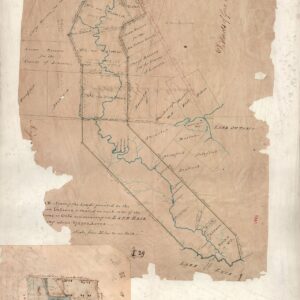

“Wee say upon these and many other good motives us hereunto moving have freely and voluntary surrendered delivered up and for ever quit claimed, and by these presents doe for us our heirs and successors absolutely surrender, deliver up and for ever quit claim unto our great Lord and Master the King of England called by us Corachkoo and by the Christians William the third and to his heirs and successors Kings and Queens of England for ever all the right title and interest and all the claime and demand whatsoever which wee the said five nations of Indians called the Maquase, Oneydes, Onnondages, Cayouges and Sinnekes now have or which wee ever had or that our heirs or successors at any time hereafter may or ought to have of in or to all that vast Tract of land or Colony called Canagariarchio beginning on the northwest side of Cadarachqui lake … etc.”

By this alone, it would appear that in 1701, the Haudenosaunee gave away pretty well all of what is now Ontario and all the way to Ohio.

The first question that should come to mind is, why? Why on earth would otherwise shrewd negotiators and powerful warriors initiate a treaty that would give all of their huge hunting, trapping and fishing territory away for nothing more than British military protection from the French?

Like with most old documents which the Crown in Right of Canada uses today to uphold its assumed title over Indian land, one has to look at supporting documentation and historical accounts that led up to and ramped down from the 1701 Treaty itself and consider what the contemporaries of the day thought and wrote about it. This is the only way to really understand its original intent.

In fact, according to Confederacy lawyer and historical researcher, Paul Williams, “To understand the issues that led to the 1701 Nanfan Treaty you really have to go back to the a Great Law.”

“It is useful to view the Confederacy as expanding and contracting,” he explains.

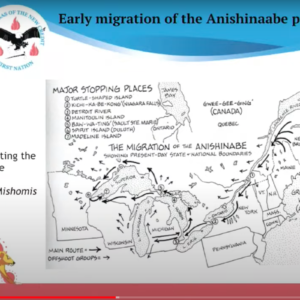

There were far flung Iroquoian hunting parties sparsely scattered throughout their beaver hunting grounds, and many temporary hunting villages were established throughout the region that would move about as that area was hunted out.

Sixty years previous to the signing of the Nanfan Treaty, the Five Nations, led by the Mohawks, had defeated, absorbed or expelled several other smaller Nations from the region and considered it land they won by conquest. The British Crown accepted that that tract of land did in fact belonging to the Iroquois. This is well evidenced by many British and French maps and records of that time and afterwards.

It was a time of expansion.

“The Nations were sometimes absorbed, like the Tutelos, Nanticokes and Delewares, for instance, but sometimes remained outside of the Longhouse, but in more of a supportive role,” explains Williams. “That’s what those wampum belts mean when you see a white belt with a purple set of diagonal lines.”

But then came a time of contraction. The wars with other tribes and epidemics brought by European settlers had decimated the population.

As required in the Great Law, black wampum were sent out with runners to the far regions of their territory, calling the Haudenosaunee men back home to the south side of the Great Lakes to defend their permanent villages and crops from encroachments from white settlers in the Ohio Valley and upstate New York.

“The record of the council of 1701 shows that peace existed between the Haudenosaunee and the Algonquins, Nippissings, Mississaugas and a number of others, of which the British was not a party to,” says Williams.

During that time the French and some of their northern Indian allies were encroaching into the unguarded hunting, fishing and lucrative fur trapping territory of the Iroquois and taking liberties to build fortified “castles” or forts. Militarily, the English did not like that either.

To their mutual benefit, the League of Five Nations entered into a treaty of protection with the Crown of Britain that would be of mutual benefit.

To the Crown, it gave them a reason to push the French out of the region which they admitted at the time did not belong to them. But as military allies to the Five Nations they could do so legally, and continue to reap the rewards of the exclusive fur trade with the Haudenosaunee.

To the Five Nations, it was a way to pressure Britain to help protect their hunting and fishing territory, which, up until then, was left to the Five Nations to defend on their own. A shrewd idea brought forth by the Chiefs themselves.

However, the British did nothing to uphold its protection agreement, which angered the Haudenosaunee leaders greatly and they complained bitterly to Britain to intervene, even sending a delegation to England to complain to Queen Anne in person in 1710.

At around the same time as the 1701 treaty, the people of Albany approached the Mohawks saying the only way to protect Mohawk land against fraudulent and abusive transactions was to put it under the protection of the Crown in the form of a Trust Deed. The Mohawks agreed and signed a document drawn up by the mayor of Albany. But when the document was translated onto paper it was in the form of a land transfer and not just for their protection.

Upon reading the document, which he ordered the mayor to produce for him, the Governor of New York was appalled and informed the Mohawks what they had actually signed. When he handed the original Nanfan Treaty document to the Mohawk delegation, they tore it up and threw it into the fire.

Another agreement was subsequently drawn up in 1726 to clarify the 1701 agreement and was signed by the Senecas, Cayugas and Onondagas, but not the Mohawks or Oneidas.

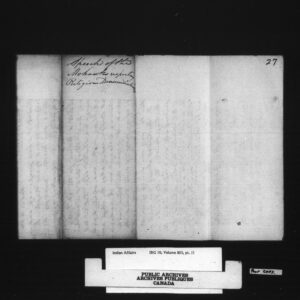

In a letter written by commander-in-chief of the 13 colonies, Major-General Edward Braddock in 1755, as recorded in New York Colonial Papers, he orders Sir William Johnson to deliver a massage to the Six Nations.

Instructions to Col. Johnson:

You are to produce to the Indians of the Six Nations a deed, which will be delivered to You by Col. Shirly and in my Name to recite to them the following Instructions.

Whereas it appears by a Treaty of the Five Nations made at Albany on (the) 19 day of July 1701 between John Nanfan, L. Gov. of the Province of New York that the said (the) Five Nations did put all their Beaver hunting (lands) which they won with the Sword 80 Years ago, under the Protection of the King of England, to be guaranteed by him to them and their use and it also appearing by a Deed Executed in the Year 1726 between the three Nations, Cayuga, Seneca and Onondaga and the then Govr. of N York that the said three Nations did Surrender all the Land lying and being Sixty Miles Distance taken Directly from the Waters into the Country (goes on to describe the boundaries of that agreement) the aforesaid three Nations with all the Rivers Creeks & Lakes within the said Limits to be protected and defended by his said Majesty

his Heirs and Successors for ever to and for the life of them the said three Nations, their Heirs & Successors forever. And it appearing that the French have from time to time by Fraud & Violence built Strong Forts (within the) Limits of the said Land, contrary to the Purport of the Covenant Chain … You are in my Name to Assure the Said Nations that I am come by his Majesty’s Order to destroy all (French) Forts and to build such others as shall protect and Secure the said Lands to them, their Heirs and Successors forever according to (the) Intent & Spirit of the Said Treaty and therefore call upon them to take up the Hatchet & Come and TAKE POSSESSION OF THEIR OWN LANDS (accent added)

— EDW. BRADOCK – (DN vol.2 pg 238).

The Mohawks did not sign this call to arms because their brother Mohawks in Quebec and the northern regions sided with the French and they did not want to fight their own flesh and blood in a whiteman’s war.

Other supporting documents regarding the Nanfan Treaty as recorded in the Sir William Johnson Papers include:

“At a public meeting with Lt Govr Nanfan at Albany, they put all their Patrimonial Lands and those obtained by conquest under the Protection of the King of Great Britain, to be by him secured for the use of them and their heirs against the encroachments and ambitious designs of the French.”

“That memorable and important act by which the Indians put their Patrimonial and conquered lands under the Protection of the King of Great Britain their “Father” against the encroachments or invasions of the French is not understood by them as a cession or Surrender as it seems to have been ignorantly or willfully supposed by some, they intended and look upon it as reserving the Property and Possession of the Soil to themselves and their Heirs. This Property the Six Nations are by no means willing to part with and are equally averse and jealous that any Forts or Settlements should be made thereon either by us or the French.”

Johnson goes on to explain, “These are their hunting Grounds, by the profits of which they are to maintain themselves and their Families, they are therefore against any settlements there because the consequence would be the driving away Game and destroying their Livelihood and Riches. Besides, part of these Lands, they have appointed for their allies and Dependents, these they want to congregate near them and by that means increase their strength, Power and consequence, for in these the Six Nations have been and are daily decreasing.”

Revisionist would disagree with what the contemporary understand of what the Nanfan Treaty was for and why it was introduced.