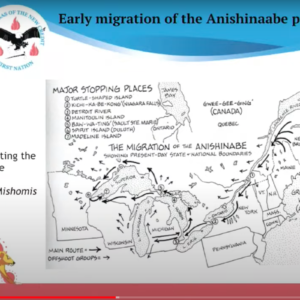

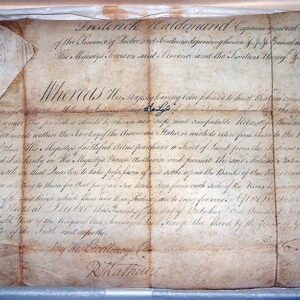

BURTCH — The tract of land known as the Burtch Tract was part of the Haldimand Tract made manifest by Joseph Brant on behalf of the “Mohawks and such others” of the Six Nations who accepted the land grant directly from the Crown in recompense for lands lost after the American Revolution. It was once estimated to be 930,000 acres, six miles on either side of the Grand River, from source to mouth.

When former premier David Peterson, promised Six Nations the Burtch lands in exchange for the removal of roadblocks on Highway #6 during the Caledonia affair, it was only the portion that was turned into an airport and training base during WWII, not for the entire 5,223 acre Tract, as mapped. Following the War, in 1949, Ottawa turned the property over to the province when became a correctional facility, until it closed in 2003.

But much earlier, David Burtch and received a 999-year lease for land on the South Side of the Grand River, directly from Joseph Brant in the very early 1800’s before Brant’s death in 1807. This became known as the Burtch Tract, with Burtch’s Landing, as Newport was once called, the access to the River.

Several pre-confederation documentations show that the leasing of parts of the original reserve (Haldimand Tract) was approved and even suggested by the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, “for the benefit of their children.”

In April of 1829, negotiations were underway between John Brant, the Haudenosaunee Chiefs, and the settlers government to surrender 807 acres to be used as a settler reserve, to place those squatters England promised to remove from their reserve lands (Haldimand Tract). The removal of squatters from the rest of the tract was a condition of the surrender.

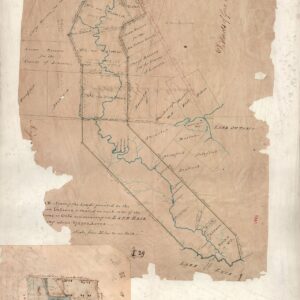

This squatter reserve later became known as Brantford, and it was also no gift. Moneys derived from the sale and lease of these town plots, as drawn up by surveyor Lewis Burwell, were to go to the benefit of the Six Nations. Many of these plots were never paid for, or if they were, there is no record of the money ever making it into the Six Nations Trust Fund established by the government to administrate Six Nations funds.

The area selected was surveyed and mapped by Louis Burwell and John Brant personally.

A mere six years later, in 1836, the Haudenosaunee Chiefs petitioned the government that they were not upholding their end of the bargain by expelling squatters from their Haldimand Tract land. This same empty promise was made by three successive Indian Agents.

At an Executive Council meeting Sept. 12th, 1840, it was recommended that Six Nations lease its Haldimand Tract land and not sell it. This would allow non-Natives to live with and alongside the Haudenosaunee while providing ongoing funding for the People of Six Nations in perpetuity.

In November of the same year, Jarvis began floating the idea of surrendering all of the Haldimand Tract, except for areas Six Nations wanted for their own, exclusively. Burtch was one of those reserved areas as were the Oxbow, Eagles Nest, the Johnson Settlement and the Martin Tract.

In fact, the entire south side of the Grand River from Cayuga to Burtch’s Landing was once set aside as part of those reserved lands talks. Almost every “surrender” of land in and around Brant/Brantford was conditional upon the removal of squatters from their land and the institution of a lease system, which would bring financial stability to the Six Nation people forever.

In subsequent years, leases were sublet and subleased over and over again until the government arbitrarily declared Brant Leases were to be turned into patents, in effect stealing thousands of acres of rightful Six Nations land and future financial security of Six Nations.

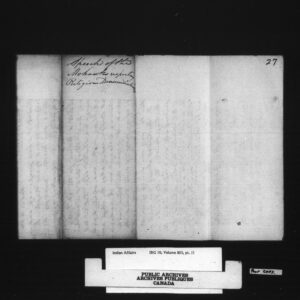

The Burtch Tract was specifically not included in the 1841 purported surrender, which has since been recognised by the government to be void. It was under heavy protest only weeks after the, so-called, surrender was signed by six, Six Nations chiefs, some with vested interest, others without full knowledge of what they were signing. By tradition and by law, all 50 chiefs were to sign any agreement that affected Six Nations lands and people.

Then, in Feb. of 1844, Jarvis comes out and frankly states that there is no way the government is going to remove squatters from the Tract.

By 1845, Six Nations Chiefs Council compromised their stand for the entire Burtch Tract, making provision for whites already settled on that tract, but insist that 2,600 acres of the Tract remain as part of the new proposed reserve.

The entire Burtch Tract is 5,223 acres, according to early surveys. Lands with improvements made by early settlers were 1,763 acres, which Six Nations were willing to discuss as a separate issue. But the government bluntly informed the Chiefs that they would not include any of the Burtch Tract in the reserve lands.

Behind the scenes, Indian Agents, and government officials, and even map maker Lewis Burwell, were promising certain settlers that they would get first dibs on the Burtch land once the 55,000 acre new proposed reserve was settled, without the Butch lands included.

Settlers with legitimate leases were informed to be ready to relocate when their leases expire.

In June of 1847, Six Nations Chiefs declared again that they do not wish the Burtch Tract to be sold. Again, on Nov. 20, 1847, Council clearly stated they would not sell off the Tract, even after the government suggested the sale would provide enough money to buy new farm implements and seed to every farmer at Six Nations.

Ignoring all Six Nations protest, Supt. General Major T.E. Campbell drew up the plans of the reserve #40, not including the Burtch Tract, on Jan. 18th, 1848.

In an 1851 report from MP David Thorburn to the Honourable R. Bruce, Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, he says that it was “with great difficulty” he got the Six Nations to sell the Burtch Tract. But there is no documentary evidence to support the notion that the Tract was ever surrendered. If it happened, it is obvious it was done without Six Nations approval or any such due process as required by British law through the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Fast forward 180 years, and the arguments and evidence regarding the Burtch Tract still have not been dealt with. But now the water is even murkier.

Since the 1840’s and 1850’s, there has been an Elected System of government brought to Six Nations mirroring British law, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Chiefs Council is in a state of disrepair, there is some misgivings over the operation of the Haudenosaunee Development Institute in acting as land agents for communally owned assets, and the Mohawk Workers, who are still seeking what they believe is their inheritance, and insist on being at least included in decisions by either party in their name.

This segment of Mohawks believe the Haldimand Proclamation was no “gift” but was made as compensation for Mohawk lands lost following the American Revolution, and was a document directed towards themselves and others of the Six Nations who wished to give up their traditional territories to join Brant in 1784. For them, neither the Elected Band Council nor the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Chiefs Council have any right to make deals with Mohawk lands without their say.

“A promise has been made that every assistance will be given the new settlement at the Grand River; a saw, a grist mill, also a church and school are to be erected, and 25 pounds to be allowed to a school teacher, whom they are to choose themselves. Lieut. Tinling is to accompany Brant in the spring to lay out the town (Mohawk village) and divide the farms.”

John Earl may have original lease. Morris Thomas gets 999-year lease from Brant.

Part leased to (Peer) of Mt. Pleasant. Northwest corner of tract (93 acres) for the remainder of the 999-year lease. A dung Fowl a year to the Chiefs.