The residential school system was a terrible period of time in Canada’s history and a lot of people are now becoming aware of it. But there was a time when even Joseph Brant might have approved of the results of educating his people. Although the objective was always the same — total assimilation and the cultural genocide of a recognizable people — most of the allegations of the many abuses and atrocities against Indigenous children came later. The following is a report from 1845.

Open letter published in a Canadian paper — maybe the Currier

Education meant to even the road

June 1845

A Visit to the Indian Institute, Mohawk, Near Brantford

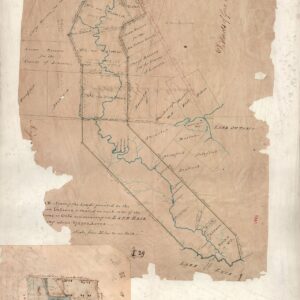

This morning, accompanied by Mrs. Nelles, I visited this interesting institution, which occupies what was the site of the Mohawk Village. It is pleasantly seated, a structure capable of containing 100 children of both sexes, with accommodation for Superintendent and family and teachers, and will, when the out-buildings are completed, from quite an imposing building.

At present there are upwards to 60, of both sexes, training for future usefulness; ; the boys as farmers and mechanics; in age varying from 17 to 7.

The system of education is the manual labour. Each inmate in rotation as at the plough, or in the workshop, or in the school; whilst the time of the girls is divided between the labours of the house and mental improvement; there, the refining, elevating power of music is brought to bear, and some are studying the piano. This, however, is after labour, and is held as the reward if industry.

I saw a youth, of perhaps 15, ploughing, which would not have discredited a man, his furrows were straight and well laid. I noticed this and he seemed pleased. Er enter the building from the front by a flight of steps, and are introduced to the comfortable apartments of Mr Ashton by Mrs. A. After a while we visited the senior school, under the charge of Mr. Barefoot, himself an Indian, but a student of the Normal School.

All are engaged, some writing, others studying geography. Here is nothing different from what would be seen in a well-organized white school. Order and diligence prevail.

Mr. A., the General Superintendent, meets us here, and courteously shows us the working if the school. Mr. A. Has a devoted life — now about 40 years — to the teaching and training of youth at home, and has been sent out by the Company which has now so long been a friend of the British North American Indian. Evidently the choice is a wise one. Mr. A. is the right man in the place. He seems to have discovered the peculiarities of the Indian mind, and to have applied his former experience of youth in this case with a success quite equal to the four years of his incumbency of the office. His object, plainly, is to raise the red man’s to an elevation so that he may successfully compete with the white in the struggle of life.

Here is duty. It is not for nought; mush less is it for the selfishness of the prevailing white that these children of theorist remain among us, seeming dependents where once they were masters. Provinces have left them to test our discharge of duty, whist weighing our obligations to the God and Father of the red and white alike.

The question must be met and answered: “Shall our Indian brother and sister be a weakness or a strength in our social system? Does not their and our best interest points to the path of wisdom, as seen in efforts like this Institute? We will not let you sink. We need your help in working out our national destiny. We will use you as an integral portion of the materials to your hands; and you, together with us, shall enjoy the rewards of success.”

I put it to Mr. A. And his answer was — “I find the Indian mind quite equal to the white, except in energy.” Here is fails; and surely a remedy can be discovered. What has made the once painted Briton physically and mentally what he is; can in fullness of time, change the red man into a very different being from what he is. You may not take an essential change; but what long civilization and religion has done for the one must greatly influence the other. And, judging from the effects already produced, the Indian’s friend has struck out a course suited to his present state — a composite education, having regard to body and mind — that roving body, that listless mind — which, if diligently pursued, will end in success.

The Indian must be taught self-reliance. He must be made to feel that to be always in the nursery — always fed from the Whitman’s table — is good for neither the one nor the other. He must feel that he is a man among men, and must no longer be a child; but, as a recognized man, to take upon himself the responsibilities of station and discharge them like any other in the same condition. And if he fail, and that failure is attributable to myself and not to [unreadable] circumstances beyond his control, he must be [unreadable] to consequences. The pampering and [unreadable] must cease in the Indian is not to be a thing or a chattel, but a man, like other men.

But I return to my impressions from what I saw. So far as such a passing visit would enable me to judge, the habits of neatness, order and self-respect inculcated (sic) were received with equal aptness as in the like class of whites. In the school there answering was quite equal. So, in writing.

The ease with which they caught the meaning of a question of address was great.

They delight in singing, have naturally sweet, harmonious voices. Mr. Ashton has adapted the Hullah system to his pupils, and with a good measure of success, judging from the specimen given. Two or three hymns were very accurately rendered and with much affect. Whether the growing practice of Indian concerts is calculated to advance him in morals, and in self-respect, is a question for his best friend to consider. Doubtless their professed object is good, but has it answered; is it likely to answer its profession!

We visit the boy’s dormitory—it is neatness and comfort combined. The rooms without doors, so as to give the freest currency to the air. Each boy with his own bed made the apartment the very home of healthy sleep.

I visited the dining room. The hour of the day, which, to hungry youth, is associated with sensations, best understood by youth, is near, the tables are spread with weapons of war, soon to be skillfully handed, which into reduce plenty to scarcity, by changing hunger to satiety.

It was soup day; and the boiler on the eve of his last duty, showed anything in preparation but soup meagre, not having received an invitation to dine I am not able to speak from experience.

After our visit to the main building we are to the manufactory of “hurdles.” This mode of fencing the farm has been rendered necessary, from parts of it lying along the Grand River and its periodical floods. But as timber becomes scarce and consequently dear, this or some other mode of the kind, will be rendered necessary. The boys are taught by an experienced mechanic to put them together; from the quickness, with which they acquire the art, may be argued the taste of the Indian for mechanics. I will only add, lest

I should occupy too large a space; and weary your readers, that Miss Fisher has a secondary education department. As we enter she is teaching some 20 of both sexes of an age ranging from 15 to five r six, simple addition and multiplication, they are tried in, and acquit themselves far better than what I would have expected; Since figures is not the Indian’s forte. However, I saw nothing of any peculiar difficulty, which cannot bereaved by persevering study and application.

In the department of numbers, as well as in any other branch of science, the Indian youth now, having a fair field without favour, may compete except it be his own fault, with his equals of every nationality for the prize of this Dominion with every hope of success.

File no. DSCF5334.