As the earth is usually covered in a blanket of snow by this time of year, the winter months are and have always been garnered as the season ripe for storytelling.

Begging older relatives for stories during the summer was usually met with “there is enough to do,” as stories told during the winter were savoured because they offered familial bonding and a certain warmth that nothing else could.

But not only were stories teaching tools but many stories were also the basis for superstitions that reinforced belief systems. Thus storytelling offered more than just connection, as tales were inspired by the world and real dangers that surrounded the ancestors that told them.

A great example of this would be the superstition to never to sing outside at night, and this belief is often linked to the story of the Seven Dancers:

As it was first written by Tehanetorens, or Ray Fadden, the story of the Seven Dancers explains how this asterism came to be.

As it was first written by Tehanetorens, or Ray Fadden, the story of the Seven Dancers explains how this asterism came to be.

Looking to the sky for the direction of ceremony shows an ancestral reverence for the stars, as the big dipper is one of the oldest constellations in the sky.

“The year isn’t new until we’ve stirred the ashes,” is an adage that follows closely with traditional beliefs on Six Nations as well. And the most sacred of ceremonies that belong to the Haudenosaunee begin at certain points during the rotation of the Ursa Major asterism, or the big dipper constellation. It is from one of those ceremonies that the adage comes from.

Wahon:nise kenha, “a long time ago,” there was a Haudenosaunee camp set alongside Lake Ontario.

During the winter months a group of seven boys living at the camp formed a secret organization amongst themselves. At night they would congregate around a small fire that they deemed a council fire in the forest near the lake.

Each night they would dance and sing under the guidance of their appointed leader and one evening, he suggested that their group should hold a feast during their next council fire. He then gave each boy a chosen food item to bring to the feast from corn soup and green corn to deer meat.

The following day, each boy approached his mother and asked for the desired food item, but each of the seven were refused. Their mothers were suspicious and told each of them that they had enough food to eat at home and that there was no need for them to carry good food away into the woods.

The seven boys returned to their mock council fire empty handed and despondent after being excited to host a feast for themselves. Their leader decided to cheer them up and teach their mothers a lesson.

“Never mind my warriors, we will show our parents that it is not well to refuse us food. We will dance without our feast,” he said.

He then instructed his dancers to dance hard, to look up at the sky while they danced and not to look back even if their parents might call for them to return.

After giving his instructions, he took his water drum and began to sing a powerful but forbidden song — in those days the hymn he sang would be regarded as a witch song. The boys danced to the drum and as the drum beats began to hasten, they seemed to forget their worries and even their parents.

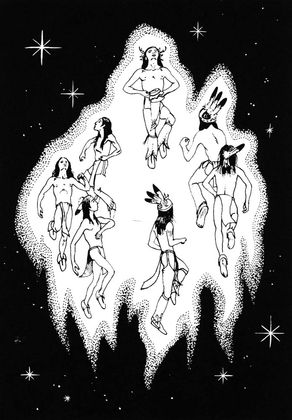

As their bodies became light, they began to rise into the sky while they danced. Their parents called for them as they reached the treetops but the dancers continued on until they reached the sky.

It is said that once they reached the sky they then became the flickering stars of the big dipper constellation, called the Seven Dancing Stars to the Haudenosaunee.

This story is often told to children as a means of explaining the constellation and as a learning tool.

When the brightest of the seven stars, Alioth, shines many older Haudenosaunee people will look at the constellation and remark “they’re dancing hard tonight aren’t they?”

This story is also where that remark comes from.