People of Six Nations want autonomous education system not run by elected council, immersed in Haudenosaunee cultural values

OHSWEKEN —A core group of over 30 Haudenosaunee educators, researchers, and cultural advisors say they have a vision for what the future of education could look like at Six Nations of the Grand River.

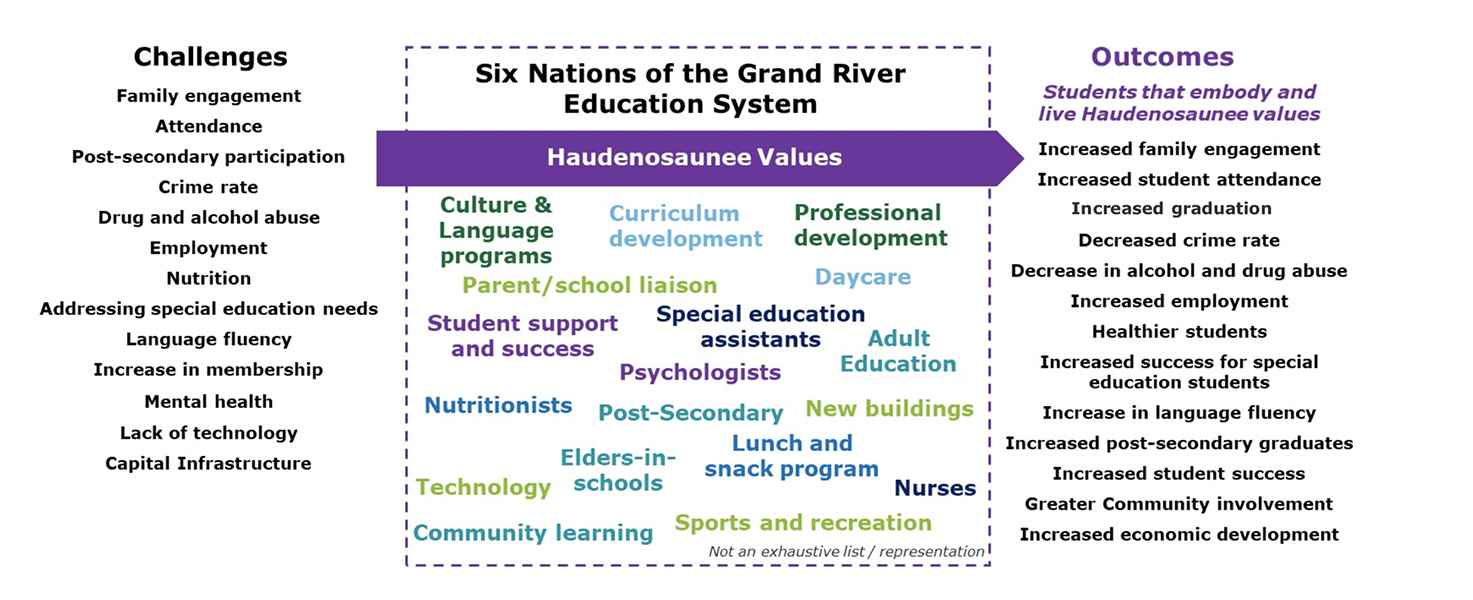

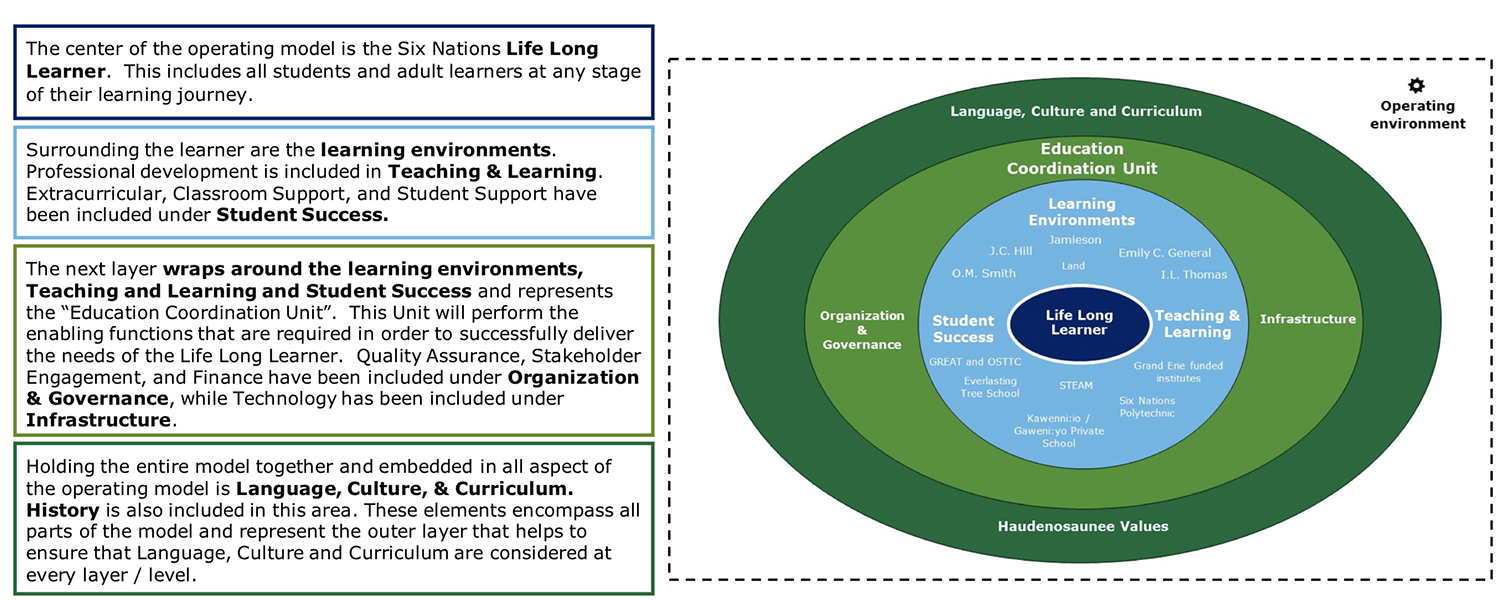

The Life Long Learning Task Force was mandated to explore options and make recommendations to articulate what a new, wholistic and inclusive Six Nations led education system would look like — and now officials say they are looking to the federal government to fund it’s manifestation.

Julia Candlish, Education Manager for the Lifelong Learning Task Force at Six Nations gave details of that vision to a group of about 100 people gathered at the Six Nations Community Hall Thursday April 4 — as well as a bit of a history lesson on what Six Nations has done in the past to reclaim authority over education its own citizens.

Candlish was accompanied by four core task force members: Elected Councillor and Task Force Chair, Audrey Powless-Bomberry; I.L. Thomas principal, Reva Bomberry; President of Six Nations Polytechnic, Rebecca Jamieson and Haudenosaunee researcher, Phil Monture.

According to Candlish, the task force compiled data collected over decades of failed negotiations with Ottawa to see Six Nations regain control over education — and put that together with new data collected in two new studies in 2018 to paint the picture of what kind of an education system people of Six Nations need and want and could have.

The Six Nations Education Engagement Report was assembled by researcher Connie McGregor — who collected feedback in 2018 from 1019 participants: teachers, parents, and students from Six Nations, from Grade 4 elementary students through to adults over 80. Her findings are compiled in a report, now posted to the Six Nations Council website.

Deloitte, a research firm, was tasked with hashing out the cost for the vision. It is a $2.2 billion need that would see everything from new schools, a residence building for Six Nations Polytechnic, transportation funding, early years education and adult learning with an immersive approach to Haudenosaunee values, culture and language.

Also proposed are a Six Nations high school, a language and culture centre, new playgrounds and funding for Kaweniio/Gaweniiyo Highschool and the STEAM Academy — as well as adequate funding for proper staff and teachers.

The task force says they added into the cost analysis mental health workers at every school on a daily basis and other staff to provide support services to students in need.

The cost analysis say the $2.2 billion need would come in over 10 years would be broken down into annual costs of $17 million for the operation of the Lifelong Learning Centre, $13 million for technology and upgrades, $21 million to run a high school, $16 million for adult immersion programs, $2 million for a language centre, $3 million for daycare and $2 million to community learning opportunities. The report says $211 million is required for capital requirements and seeks to double current expenditures of K-12 education.

According to Candlish attempts have been made since 1972 to create an independent education system at Six Nations but Ottawa was consistently coming up short financially and offering short term funding packages that wouldn’t guarantee the community’s needs would be met.

“It started with the Indian Control of Indian Education in 1972,” said Candlish. That assertion was made by the National Indian Brotherhood, now known as the Assembly of First Nations. “We wanted to bring up our children to know their culture, know their language and things like that,” said Candlish.

Ottawa’s reaction was to develop a devolution process, granting reserves in Canada a mechanism to claim administrative control over their schools.

“There are 634 First Nations in Canada,” said Candlish. “At that time three of those communities did not go for that devolution deal — Six Nations, Coal Lake in Alberta and Bay of Quinte. We didn’t want administrative control only.”

The problem, Candlish says, is that ever since refusing devolution Six Nations has had continuous efforts to recover control over education at the community level without success.

“What we’ve been looking for is always different than what the federal government has been offering,” said Candlish. “Every time we went to the federal government and said ‘this is what we want – this is what we need’ they wouldn’t give us enough money. Every time that was the barrier — they wouldn’t give us enough money to do what we needed to do.”

Those needs included funding for transportation, cultural and language learning, special education, extracurricular activities and more.

In 2014 the federal government proposed the First Nations Control over Education Act which was widely rejected across Canada. “It actually gave the federal government more control over First Nations schools,” said Candlish.

Further offers were put on the table between 2016 and 2018 to fund education at Six Nations but none of those offers measured up to the specific needs at Six Nations. “For us we looked at all of these things and we don’t really like any of those options,” said Candlish. “We don’t want to fit into their box.”

“We’ve done analysis on all of those different options and none of them work for us. So what we’re doing now is a little bit different than all of the efforts previously. It’s more holisitic. It’s based on our needs of learners in the community. It looks at the full continuum of lifelong learning — it’s not just based on K-12 education,” said Candlish.

Elected Councillor Audrey Powless-Bomberry is the chair of the Education Committee and sits on the Lifelong Learning Task Force. She says it’s taken two years of research and learning the landscape of education on First Nations communities across Canada to find a pathway forward for Six Nations.

Powless-Bomberry has 42 years of experience as a teacher, principal and vice-principal at Six Nations schools and has an organic understanding of the history, victories and gaps in education services at Six Nations.

“We want to have a community system – not a school board. It would be a coordination body. It will be done in consultation with everyone. We’re looking at full control over lifelong learning. We’re not devolving because we don’t want the same deal as other first Nations. We want our needs met at Six Nations. And we want a system that meets the lifelong learning needs of our community, and our languages and our culture,” said Bomberry.

Bomberry said survey respondents want to see an autonomous coordinating body independent from the community’s governing bodies.

“The community does not want elected council to run education,” said Bomberry.

Candlish said, “There are some who have singed agreements in Manitoba, BC and Nova Scotia and Ontario — some under inherent rights policy and self governance agreements, some under regional education agreements and one is the establishment of a school board like entity under a program that the federal government had. You have to follow the policy to get there. What we’re saying is we’re not following any of those policies — we need something different.”

Candlish and Bomberry said the task force is seeking a perpetual funding agreement straight from the treasury, bypassing Indigenous Services Canada altogether. The current task force is hoping to secure a memorandum of understanding with the federal government for funding Six Nations own stand alone education system this summer.

I would personally like to see the plan for action based on these needs. Recomendations were made back in 2005 by The Education Comission and I am wondering if those recomendations were updated and if so what are they? Several other questions – 1. How much has been set aside for corriculum developement and AQ courses for many of the teachers here at Six Nations who know little about our culture and ways of knowing? 2. Has resources for relevant cultural content been included? 3. Has there been consultation and financial disclosure been saught for the cost the porvincial government has spent in the last decade to include indiginous content in corriculum? 4. How does this project align in the recomendations set forth by the TRC.