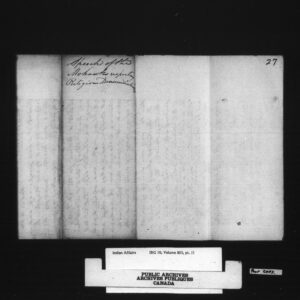

OTTAWA — It is a long and boring process for those not so inclined, but to those of us who have a gluttonous curiosity for such things, searching through the Canadian Archives can offer the researcher the occasional nugget of truth.

Hidden in plain sight there are tens-of-thousands official documents and archived letters of correspondence between British government representatives and the indigenous peoples of Canada.

This kind of archaeology doesn’t require a trowel and shovel, it only takes a computer and a lot of persistence. Every shovel full of documents located in the National Archives of Canada, has to then be sifted through the screen of your personal search objective. Once you think you may be on to something, the real search begins.

Sometimes you will find a letter or a report that seems out of place. Some have thought these possibly incriminating documents have been hidden on purpose, but more than likely, they have simply been misfiled.

The latest round of inquiry into the misguided Residential Schools experiment involves the search for the unmarked graves of thousands of young Indigenous children who died while attending most of these, so-called, schools.

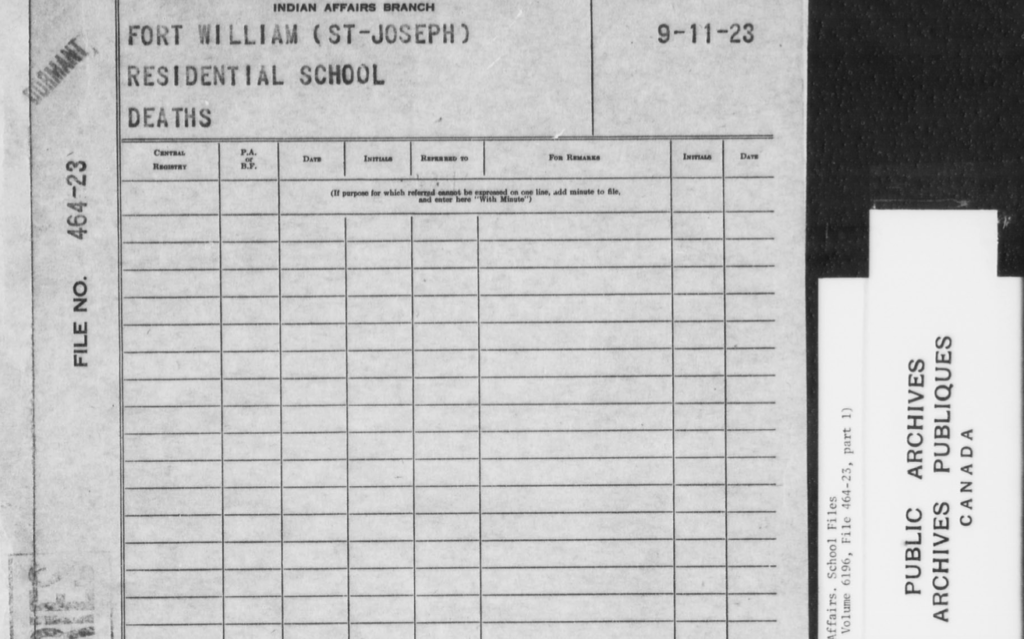

It was required by the Indian Affairs Department that an official form was to be filled out and an inquiry conducted in each case. The main focus recently is the search for Indigenous children’s remains buried in unmarked graveyards connected to these schools, But, there is also a push from many Native leaders to find and repatriate the remains of some of these children to their own people.

There are names and school numbers of many of these unfortunate souls along with a brief report of how the child died.

There was a per-capita payment made from the government and church to each of these schools. Keeping track of the numbers would have been necessary to get the maximum allotted payment to run the schools and pay the teachers and priests.

Searching for something that may have already been purged or put away in secret classified files, can be tenuous, but like following the 1849 California gold rush, the occasional nugget is still can be found. Panning out the sands of time is what it takes to find the precious material left behind.

Like one report filed April 30, 1940, which reports to the Department of Mines and Resources, the death of Martha Kashkeen, student Number 51, enrolled at the Fort Williams Residential School, Long Lake, Martin Falls band.

This report states that Martha died on April 4th, at the KcKeller General Hospital yet was not reported until April 30th. The name was then added to a form that has space for 26 names, per page. File Number 464-23.

Young Martha reported feeling sick to the school nurse and was given an aspirin and a laxative with a hot water bottle for her bed.

Still very sick, Martha was taken to the hospital the next morning. It was quickly stated that she was sent by car which didn’t cost the department any money. There she died.

Michael Charley Macheegabow, pupil number 199, died of Meningitis in early 1937 after being sent to the hospital from the Kenora Indian School.

Almost a year later, on Jan. 15, 1938, student John Jack He reported being sick on January 2nd and put to bed with an aspirin and a teaspoon of Epsom Salts. He was taken by sleigh to hospital where he died of influenza after falling into a Coma. In this case, the parents were called and came 100 miles just in time to watch their son die. Another boy died around the same time with what was described as “sleeping sickness.”

Also in Kenora, on June 27th of the same year, Nancy Keewatin Pupil number 0262 fell sick with a pain in her side, January 10th. She remained sick, not responding to the basic meds administered at the school, until she was transported by car to the hospital on May 29th, where she remained until her death in June.

Orphan, Nancy Keewatin died of T.B. at the Kenora school in July of 1938; Rosaline Bird, of the Whitefish Bay Band, died of T.B. June 26th, 1941, after two trips to the St. Joseph’s hospital. This report states that Bird’s body was buried in the school cemetery.

There was a standard form in which school principals had to record the basic details surrounding the deaths of residential school students. Each page had room for 28 entries. Every school was issued these forms and dutifully filled them out, absolving any blame towards the school or any of its staff. It is hard to find them because these forms and reports were mixed in with day-to-day activities and receipts.