Almost 15 years have passed since a Canadian judge ruled in Brantford court against Six Nations land protecters, the Elected Council and the hereditary chiefs.

In his reasons for judgement, he asked why Six Nations had never complained about the sale and development of the land in question until recently. Why that verdict was not immediately challenged is still a bit of a mystery, but they accepted the judgement, paid the fine and quietly walked away.

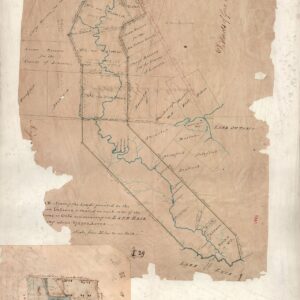

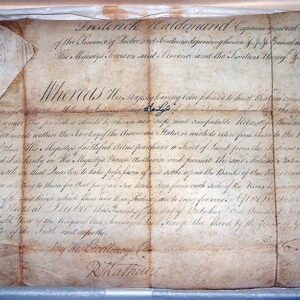

The issue of Six Nations’ ownership of Haldimand Tract land has been a marathon debate since the Mohawks, under the leadership of War Chief Joseph Brant, accepted the reward of a new land, six miles deep from the “spring” to mouth of the Grand River, as worded in many early documents.

As familiar as many of us are regarding that point, it is never a bad idea to go back to do our best to understand the times, the deceptions, and ultimately, the misguided trust of the Six Nations.

Historical records provide proof that government officials of the time knew exactly what they were doing when they arbitrarily ignored, then hid the original intent of General Haldimand’s grant to the loyal allies under Joseph Brant. After all, Haldimand was then dead and couldn’t answer these questions himself.

The following are only a few of the examples found in the Canadian and British archives that may played a part in our better understanding of how it all went down.

But there are many documents and personal communications left behind which clearly show both the intent of Haldimand and Brant when they drew up the wording of the Haldimand Deed together. In contrast there are letters and communications at government levels to suggest the intent by others to claw back the terms they agreed on.

Haldimand was not the only one wanting to make good on the promise made by his predecessor Guy Carleton when he promised full recompense to lost lands following the American Revolution.

In 1783, Lord North, who was the Crown’s first minister in Britain, wrote Haldimand saying,

“The people (Six Nations) are justly entitled to our peculiar attention, and it would be far from either generous or just in us, after our cession of their Territories and Hunting Grounds to forsake them. I am, therefore, authorized to acquaint you that the King allows you to make those offers to them, or to any other nations of the friendly Indians, who may be desirous of withdrawing themselves from the United States, and occupying any lands which you may allot to them within the Province of Quebec (Canada) …”

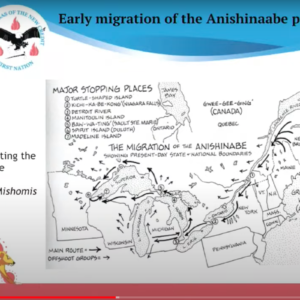

Brant chose the Grand River tract which would put them closer to the Seneca and other allied Nations who chose to stay back in the newly formed USA.

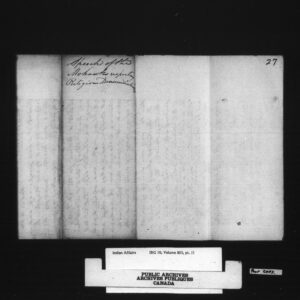

By March of 1791, Brant continued petitioning for an answer as to the status of the Haldimand Tract land. This time he contacted Lord Dorchester seeking clarity.

“The Deed or Grant for the land here which you are going to give us, we hope you will make the Deed or Grant, near the same sort which General Haldimand first promised us, we hope the Council will not restrict us too much … otherways (sic) we shall look upon it not much better than a Yankee deed or grant to their Indian friends.”(1)

Peter Russell, Administrator of Upper Canada, wrote the Duke of Portland in July of 1797, reporting that Brant was getting more forceful in his inquiries on behalf of his people.

“Had the Five Nations conceived the lands on the Grand River were given to them upon any other footing than that on which they formerly possessed those on the Mohawk River, they would never have come to settle in this Province,” he warns. “That they were a free and independent Nation; … That their affection for the Father the King of Great Britain had induced them to leave a most fertile Country every way competent to their Support, in order to live under His Majesty’s Protection, as they disliked the people who inhabit the Country they had forsaken; That Sir Frederick Haldimand had received them with open arms …. That they then considered this Gift as a free unequivocal Grant of Country, with every power over the disposal of it, which they had over their lands on the Mohawk River. These they could sell or give away at their pleasure, and they conceived that their power over the Grand River land was the same. When White Men had informed them that they were mistaken, they applied to Lord Dorchester and to Governor Simcoe for a new Grant. This was promised them; and a Grant had been offered to them by Governor Simcoe which they rejected, because it did not convey this Power. They were promised that their requests should be laid before their father the King.”

There is so much more to be gleaned from readily available historical documents which help to explain not only what happened between the 1784 Haldimand Deed and the 1793 Simcoe Patent, but more importantly, why and by what means. A hundred years from now, what will the archives show about the government’s real reaction to Six Nations’ land protests in Caledonia and elsewhere?