BRANTFORD — A developer is taking a second kick at the can, again asking the city of Brantford to change a zoning by-law to allow it to build a condominium development area over the site of a Six Nations ancient village site. A site that they already know is environmentally sensitive, historically important to both Six Nations and Mississaugas of the Credit — and geologically critical to the Grand River.

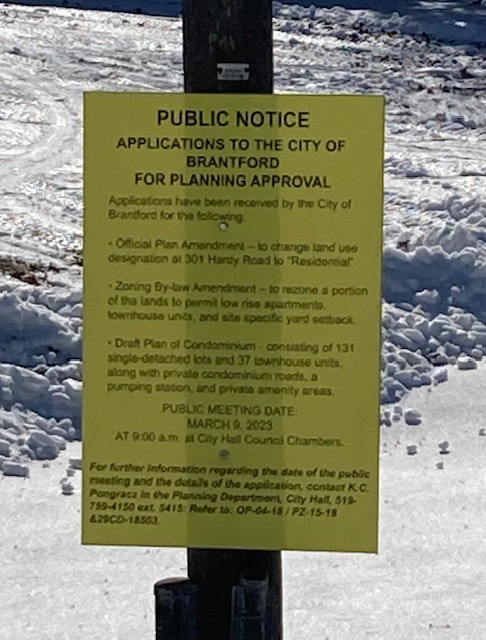

A notice posted to a property on Hardy Road in Brantford’s north end, just outside Paris, shows that Sifton Properties is looking for clearance to build a neighbourhood of condominiums over the historical village of Davisville.

A public meeting about the proposal is set for March 9.

The property, and the proposal to build condos there, was part of a massive fight between the City of Brantford, Sifton Properties and Grandview Ravines Inc in 2012-2013 with the Ontario Municipal Board after city council resisted the developers building over what the city’s waterfront master plan then identified as an ecologically sensitive area.

Developers Sifton Properties Ltd. and Grandview Ravines Inc. appealed to the OMB, claiming the applications were being delayed as city officials made changes to policies that would prevent their development from getting the green light.

That fight cost the city of Brantford more than $2 million dollars over nearly a year of hearings.

Six Nations Men’s Fire became involved in the proceedings to voice community opposition to the development and bring forward issues around the importance of the site to Six Nations.

Professor Gary Warrick of Laurier University, Brantford Campus, was one of the defence witnesses called by the City of Brantford.

Warrick studied the Hardy Road area since Davisville’s exact location was discovered in the late 1990’s by retired archaeologist Ilsa Kraemer and says Davisville was a thriving Indian village along the banks of the Grand River, established by a Methodist Mohawk Chief, Thomas Davis, around 1800.

Davis and a group of fellow Mohawks disapproved of the Anglican teachings of the Joseph Brant Mohawks at the original Mohawk Village and, what they considered to be the negative moral conditions the village had fallen into since being established in 1785. Davis led a group of discontented Mohawks to establish a new village upstream in what is now the Hardy Road region of Brantford’s Northwest.

Peter Jones, son of pioneer surveyor Augustus Jones, like his father before him, married a Mississauga woman. He converted to the Methodist faith in 1823, and became good friends with Chief Davis, visiting Davis’ Hamlet, as it was also referred to, often.

Jones eventually invited several Mississaugas of the Credit River near present day Toronto, to join Davis‘ community, which many did, and lived separate from, yet jointly with, the Mohawks at Davisville.

After several years, the Mississaugas pulled out and moved back to their traditional home on the Credit River, until resettling on a corner of the Six Nations reservation, which was given to them by the Six Nations Confederacy.

Due to upriver clear-cutting by settlers in the establishment of Kitchener and Guelph, the river began flooding its banks downstream by 1833, and washing out the cabins of Davisville residents. The site was abandoned and the Davis Mohawks resettled in Sour Springs and elsewhere, but not many returned to the Mohawk Village.

In around the early 2000’s, further excavations revealed the size and extent of the village as being bigger and wider ranging than originally thought. Most of this area has been the subject of Warrick’s digs and Timmins-Martel’s surveys with eight identified sites strung out along the banks of the river. But there could also be more sites yet to be discovered, because along with the Davisville remains of the 19th century, there were also artifacts proving habitation in this gentle bend in the river may go back as much as 12,000 or 13,000 years as well as evidence of other habitations over the centuries since.

Warrick recommended to the OMB that certain areas within the Sifton plan could disturb the historical and archaeological significance of this very special and important site.

“A combination of archaeological and natural features form a significant cultural heritage landscape would preclude development of the properties in question,” he writes. The area is so rich in archaeology that Warrick and Timmins-Martel together have catalogued 80,000 artifacts in an area of only 1200 square meters. Where people lived, they also died, creating highly sensitive ancient burial grounds throughout the region from all inhabitants over the past 12,000 years.

“The accumulation of archaeological evidence indicates 10,000 radiocarbon years (12,000 calendar years) of Aboriginal use and occupation of this portion of Brantford, and holds tremendous value for the Mississaugas of the New Credit and Six Nations of the Grand River,” writes Warrick. “In the Davisville area, the density of archaeological sites rivals that found in the Mississippi River valley of the central United States, one of the richest archaeological areas in North America.”

Aside from the historical and archaeological arguments there is much evidence of unique and rare geological elements such as Tufa mounds in the region. Tufa is a rare rock formed by highly mineralized water, rich in calcium carbonate, bubbling to the surface and congealing into a porous, light grey stone which early settlers of this region used as foundation stones for barns and outbuildings, some of which are still evident today.

There are water geysers, nearly extinct plant life in the area, as well as endangered species, which call the Davisville area home.

The public meeting about the Hardy Road proposal will be held March 9, 9:00 a.m. at Brantford’s City Hall chambers.