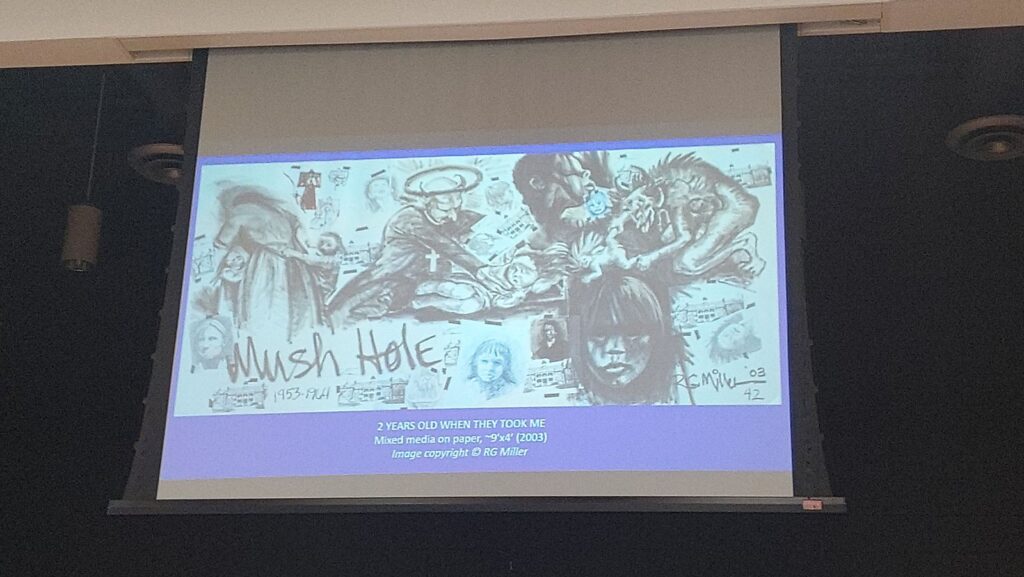

His haunting art – a collection called The Gary Miller Art Project – played on a projection screen behind him while he spoke of his experiences at the Mush Hole.

It all focuses on his experiences at Canada’s most notorious residential school – the so-called Mush Hole in Brantford, Ontario.

Gary Miller attended the Mush Hole for most of his childhood. He began attending when he was only three years old.

“Some people say the nickname ‘Mush Hole’ came from the bad food they served the children but I think it’s because of what they did to our minds: turned them into mush,” Miller says.

He spoke of his horrifying experience at the Mohawk Institute in Brantford during the second annual general meeting for the Six Nations Survivor’s Secretariat on Tuesday, not mincing a single word about the abuses he and his peers suffered.

There was complete and utter and silence from those in attendance as he spoke.

Blue-eyed and fair skinned, his nickname at the Mush Hole was Whitey.

To this day, he’s still called Whitey, but he says he doesn’t care.

“They’re just jealous of my blue eyes,” he joked. “Too bad.”

His sense of humour is commonplace among residential school survivors who were forced to develop a biting wit to cope with the taunting and verbal abuse most children faced at the school.

The Mush Hole was a place of starvation, physical, sexual, spiritual, and emotional abuse according to thousands of children who attended.

Their main escape, Miller said, was going to the city dump.

“We used to love going to the dump.”

They’d sneak down the long, winding driveway at the Mohawk Institute under the starry night sky and head to the city, searching for their favourite treasure – candy.

“You could never beat that,” he said. “That was awesome.”

The local candy factory – Weston’s – would bring candy to the Mush Hole for the kids once a year.

But that didn’t compare to the haul the kids would find at the dump – sometimes boxes of it.

“We liked boxes of candy,” said Miller. “We’d stash ‘em in cornfields. They were thrown away.

It didn’t matter to us. We’d just clean them off in the creek on the way home – the dirty, filthy creek. It probably made our immune systems healthy. I rarely get sick. You just wiped off the white powder to kill rats, clean it in swamp water; we didn’t care – candy’s candy, man.”

Going to the dump was their escape. It was their escape from the constant and ever-present prospect of sexual abuse from the nuns and priests who made up the staff at the Mohawk Institute.

“It was better to go out and sneak to the dump than have somebody sit on your bed and take you into their room and have their way with you,” Miller said. “It was like having a menu, having a choice. A lot of us don’t like to talk about it.”

It’s been said that residential schools were created with the intent to “kill the Indian in the child.”

But Miller says it was worse than that. Much worse.

“It was kill the fu*king Indian, period.”

When he eventually left the Mush Hole, like so many other survivors, he turned to drinking, hanging out at bars in urban centres, learning how to fight, his heart filled with hate.

“We got out of the Mush Hole. We ended up in the Silver Dollar, drinking, staggering down the streets with no use to our reserves. We’d leave the reserves. Fu*k that.”

For a time, he wanted to kill his abusers. There’s a part of him that still hates his abusers.

But it’s all been channeled into his art.

And despite all the abuse and pain that still lingers, he doesn’t want to erase any of his memories.

He does’t want the Mush Hole torn down.

“It’s a living monument,” he said.

Miller eventually got a post-secondary degree and became a talented artist, channeling all of his pain, rage and hatred into his art.

He also sobered up.

Life goes on, he said, but the Mush Hole will forever be a part of him.

“After being in the Mush Hole, you think it’s your forever place.”

All of the perpetrators of abuse at the Mohawk Institute are now gone. They may not have faced justice during this lifetime. But all of the survivors at Tuesday’s event agreed: those perpetrators are answering to the Creator now.