Of the 1843 people who settled at Grand River after the American Revolution, there were two people groups who arrived here in 1784 who identified as Aughugos: Oghguaga Joseph’s Party of 49 people and Oghquagos who numbered 113.

Those two parties settled in two villages along the Grand — one just north of the village of Onondaga and another right at the Oxbow, beside the Mohawk Village that was near the Mohawk Chapel. This was also the site of the first Six Nations council house prior to it being moved to Ohsweken in the 1860s.

One thing that is not talked about widely is the arrival of the Oghquagos. Who are they and why were they permitted to settle with the Six Nations along the Grand if they were not one of the Six?

You may remember the reference to this ancient village in the Haldimand Pledge of 1779 where the Governor promised to compensate the residents of this particular village for the destruction of their homes and their losses by American rebels — though he then spelled it Aughugo.

The village, known as Onoquaga, and referred to throughout history with over 50 different spelling variations — was the southernmost village in the Six Nations territory. Historians say the name of the village meant “place of the wild grapes”.

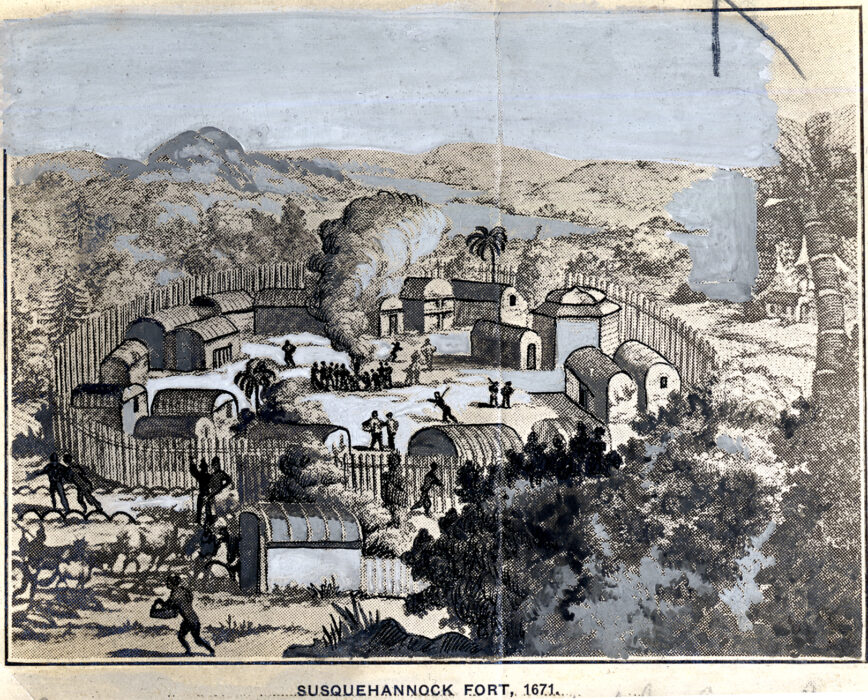

Onaquaga is located on the Susquehanna River at the bottom of what is now New York State just above the border to Pennsylvania.

Because of its location, southeast of the Finger Lakes on the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers it was a central trading hub for the entire region and because that trading hub was controlled by Oneidas and Tuscaroras for over half a century it was a major stronghold for the Iroquois economy. Prior to it being an Iroquois community it is recorded as being a Susquehannock community.

Prior to its destruction in 1779 during the Sullivan Campaign, American officers called it a ‘metropolis’ and noted it was one of the most beautiful villages they had ever seen. It had an estimated population of between 700-1000 people. An Oneida village was located around the island in the Susquehanna. Tuscarora villages were to the north and south along the river. A council house was situated on the west side of the river. Surrounding the central Oneida village were other satellite villages of Mohicans, Mohawks, Nanticokes, Tuscaroras, Susquehannock and Delawares along with other smaller refugee hubs for white and black people.

It was technologically constructed for trade and food production — surrounded by agricultural fields, orchards and gardens as far as the eye could see with at least one fishing weir in one of the Tuscarora settlements that allowed for the obstruction of passing fish to make them easier to harvest.

Missionary records show that in Onaquaga each home had a garden filled with corn, beans, watermelon, potatoes, cucumbers, muskmelon, cabbage, turnips, apple trees, parsnips and more. Farms were kept with cows, pigs, chicken and horses.

It was located on an Old Warriors Trail from Scranton to Onaquaga and was a central village for indigenous people to conduct business in for over a century sending trade not only to the north but also east to west into territory occupied by other nations not affiliated with the Iroquois Confederacy.

In the 1730s, Sir William Johnson set up a trading post there. And through the 1740s to the 1770s it was a place where missionaries came to minister and teach English. Several of the families there were Christians — including the family of Joseph Brant’s first wife, who was the daughter of one of the Chiefs of Onaquaga. They lived in a family longhouse in one of the Oneida villages there. Brant used Onaquaga and it’s neighbouring village Unadilla as the base for his operations with the British during the American Revolution.

Historical records show that Indigenous refugees who were fleeing encroachment and oppression by settlers often fled to Onaquaga and set up safe homes there. As did some escaped African slaves who also were fleeing north.

All of this boils down to something critical to note: Onaquaga was important. Very important. It was multi-national. It was a place of friendship and trade between people of different backgrounds and traditions. It was the final resting place for indigenous people of many different nations: Mohawk, Oneida, Delaware, Munsee, Tuscarora all have burial sites at Onaquaga.

But Onaquaga is noted as separate from the Six Nations Confederacy in historical records. Perhaps due to its multi-national identity. The Onaquagan’s are not a recognized people under the HCCC and do not have a sitting chief or titles under their current roster. And unlike the Tuscaroras, they are not backbenched and represented by the Cayuga Chiefs according to the adoption of nation processes.

And yet — they were noted as a distinct settling group who set up a village here at Grand River.

Throughout history they are recognized as distinct peoples. Not Oneidas, not Tuscaroras — but separate in Haldimand’s files. Though Onaquaga may have been politically affiliated with the Oneidas, when loyalists came to settle at the Grand River they were not identified as Oneidas — or by their nation or clan identity — but identified by their matrilocal connection to the village of Onaquaga.

In addition, Onaquaga’s losses were specifically articulated in the Haldimand Pledge of 1779. They were the very definition of ‘such others’ in the Proclamation. Politically important and counted among the Iroquois allies to the British in the Revolution, officially affiliated with the Oneidas while they were living in Onaquaga — and yet not a part of the Six Nations proper after the village was destroyed during the Sullivan Campaign in 1779 — razed to the ground by Rebels by fire. The orchards, storehouses, homes — turned to ash.

And still in spite of their diversity, the Onaquaga were still important and connected enough to the loyalist war efforts among the Six Nations that they were granted the right to settle their families directly adjacent to the Mohawk Chapel and Council House.

The descendants of the Onaquaga are some the inheritants to the Haldimand Proclamation — but who represents their interests today?